Welcome to the reality of Russia’s 2014 Winter Olympics!

$50 billion in costs. Pervasive corruption. Excessive delays. Human rights violations. And more...

Curious how that happened?

$50 billion in costs. Pervasive corruption. Excessive delays. Human rights violations. And more...

Curious how that happened?

Get informed Read information and check off 13 or more sites

Test your knowledge Take the quiz and win a gold medal by answering 10 or more questions correctly

The 40,000-seat Fisht Olympic Stadium is the biggest and most expensive stadium in the Olympic Park, with its cost amounting to $780 million. The stadium will host both the opening and the closing ceremonies of the Olympics.

The construction of Fisht began in 2010, one year later than originally planned. One of the reasons for the delay was the modification of the architectural concept: instead of the original project design, according to which the stadium would have resembled a Fabergé egg, designers, inspired by the panorama of the Caucasus Mountains, decided to use mountain stylistics and named the structure Fisht after a peak. The construction budget tripled from $260 million to $780 million, which, according to experts, is approximately three times more expensive than the cost of building similar stadiums in other cities. The budget increase was so steep that in the summer of 2012, law enforcement bodies initiated a criminal case that charged that the developers had overstated the cost by more than $180 million. However, the investigation has not yet brought any results.

The problem of relocating the residents of 12,000 private houses that fell within the stadium construction zone was named as the official reason for the delay. For two years, people had refused to leave their residencies, despite considerable monetary compensation that was offered to them. As a result, remaining families were evicted by a court order. The construction was supposed to be completed by summer 2013 in order to give ceremony planners ample time to rehearse. However, deadlines were repeatedly postponed, and as a result, Fisht was not put into operation until December 2013.

The erection of the Bolshoi Ice Palace, with a capacity of 12,000 seats, marked the beginning of the construction of athletic facilities for the Sochi Olympic Park. Engineers were immediately faced with the difficult geological conditions of the Imereti lowlands. This area used to be a wetland, and consequently, its current composition is a mixture of soft soil and peat deposits. This fact, which is well known to local firms, came as a surprise to construction companies from different regions. The project had to be completely reworked, with the initial plan of setting the foundation on piles replaced by a plan for an enormous concrete foundation pad, for which 40 percent of all the allocated concrete was used.

The initial cost of the palace was estimated at $200 million. However, by the end of the construction, the cost amounted to $300 million. The management of both the Mostovik Company, which was the developer of the project, and the state corporation Olympstroy are suspected of deliberately overstating the cost of construction of not only the Bolshoi Ice Palace but also other Olympic facilities. The Palace began operations in December 2012—eight months later than originally scheduled.

After the Olympics, the Palace is supposed to be put under the supervision of Russia’s Ministry of Sports. The facility either will be converted to host tennis or basketball competitions or will be used as an entertainment center. The idea of creating a Sochi hockey team, which would participate in the Russian open hockey championships, has also been put forth.

One curious detail is worth mentioning: in 2013, the Russian hockey team refused a proposal to use the Palace as its training camp because of the stadium’s excessively high rent—Olympstroy is asking around $50,000 for one day.

The 12,000-seat Iceberg Palace will host figure skating and short-track speed-skating competitions. The construction of the venue began in September 2009. Although initially supposed to be completed by October 2011, the Iceberg Palace opened for operation in September 2012—one year later than expected.

The initial amount of state investment in the project was estimated at $100 million. However, the cost continued to grow, especially as the project neared completion. As a result, expenses reached approximately $300 million.

The question about how the Iceberg Palace should be used after the Olympics represents another point of contention. The building was designed to make it possible for it to later be dismantled and moved to a different city. However, this idea has been abandoned. Another plan proposes converting the arena into a cycling velodrome. However, after a series of test events, the Russian Figure Skating Federation advanced an initiative to subsequently use the arena as a training base for figure skaters. The future of the Iceberg Palace has not yet been decided.

According to initial plans, Shayba, the small ice hockey arena designed to accommodate 7,000 spectators, was supposed to be dismantled after the Olympics and moved to Vladikavkaz. However, this plan was abandoned when Uralskaya Gorno-Metallurgicheskaya Kompaniya, Russia’s second-largest copper producer, owned by one of the country’s richest businessmen, Iskander Makhmudov, became the project’s investor. Moving the arena to Vladikavkaz would have cost almost as much as building a new one.

The initial projected cost of the Shayba arena was around $30 million. However, in the end, more than $100 million was invested in the project. In February 2013, the investors decided to make a gift of the arena to the state in order to shift maintenance expenses. Consequently, the discussion about how to use the venue after the Olympics was restarted. Governor of the Krasnodar region Alexander Tkachev and Russian Sports Minister Vitaly Mutko suggested that a circus tent be erected on the foundation of the arena. President Vladimir Putin, however, rejected this idea and ordered that the ice arena be reconstituted as an all-Russian children’s sports center.

The Adler Arena ice-skating center is an 8,000-seat roofed stadium covering an area of 50,000 square meters. Initially, the construction of the arena was supposed to be sponsored by investors, including Mikhail Gutseriyev’s RussNeft oil and gas company. However, the company later refused to finance the project, and it became the responsibility of the Omega Construction Technology Transfer Center, owned by the Krasnodar regional government. The Olympstroy corporation also invested in the construction.

Very little information is available from open sources about how the financing is being carried out. According to different sources, however, the cost of the Adler Arena was initially estimated at $32 to $45 million, whereas the final cost of the project, according to Vedomosti newspaper, amounted to $230 million. In his expert report Winter Olympics in the Subtropics, opposition leader Boris Nemtsov estimates the cost at $200 million. Thus, the cost of the project increased during construction by seven to eight times. Once the Olympics are over, the arena will be converted into the largest exhibition center in the south of the country, Sochi-Expo.

The Ice Cube is the Olympic Park’s most miniature arena, accommodating only 3,000 spectators. This is Russia’s only arena specifically designed for holding curling competitions. The investment story of the Ice Cube is rather interesting.

In 2007, there were plans to allocate approximately $15 million from the federal budget for construction of the arena. However, two years later, it became evident that these costs were being exaggerated, and the government tried to tame Olympstroy’s appetite. The state corporation then decided to reduce the amount of state financing on which it relied and tried to attract private investors.

The little-known construction company Slavoblast decided to invest its money into the curling arena. According to Kommersant, 40 percent of Slavoblast belongs to Alexander Svishchev, the owner of several metal-trading companies and head of the North of the Arctic Circle division of the Mountain Ski and Snowboard Federation. Curiously enough, the head of Russia’s curling federation happens to be State Duma deputy and entrepreneur Dmitri Svishchev, who is also the head of the Moscow division of the Mountain Ski and Snowboard Federation.

Under Slavoblast, construction expenses went up again, reaching $50 million. Nevertheless, the construction deadline was missed, and consequently, Russia’s curling championship, which was supposed to take place in December 2012, was canceled.

Initial plans for the Ice Cube arena called for it to be dismantled after the Olympics and moved to Rostov-na-Donu. Later, however, these plans were abandoned. After the Games, the sports “interior” of the Ice Cube will be moved to Moscow and the exterior structure will be converted into a multipurpose sports and entertainment center.

The planned media center, measuring 150 square meters, will be the largest in the history of the Olympic Games and will be able to accommodate 15,000 media representatives. Initially, it was intended that Oleg Deripaska would finance the construction through his various holdings. The businessman, however, refused to participate in this project, which then became the responsibility of the OMEGA Construction Technology Transfer Center of Krasnodar Krai. Open sources do not supply the construction cost of the facility.

The construction of the media center, with an adjoining hotel for journalists, began in 2010. The project was supposed to be completed by February 2013. However, the schedules were disrupted—as usual. The official facility commissioning took place in August 2013, during President Putin’s visit to Sochi. However, work on the interior and communications was not completed at the time. The media center was finished in January 2014.

The construction attracted the attention of Human Rights Watch, which repeatedly issued reports documenting systematic violations of workers’ rights, such as overdue salaries and difficult working conditions. In some cases, Central Asian migrant workers’ identity documents were confiscated, which, according to a special report by the U.S. Department of State, is considered the “use of slave labor.”

After the Olympics, the media center will be converted into one of the largest shopping and entertainment complexes in the south of Russia.

The Olympic Village in Imeretinka is a project of businessman Oleg Deripaska’s Basic Element Company. The project includes two hotels and more than 3,000 apartments, covering an area of 170,000 square meters. Investment is estimated to be $1 billion. Athletes and International Olympic Committee members will reside in this village during the Olympics.

During construction, Basic Element suddenly faced problems borrowing money from state-owned Vnesheconombank. Initially, the bank was supposed to cover 70 percent of the investment. However, later, the bank loans increased to 90 percent. Deripaska tried to further increase the amount of state loans to cover 100 percent of investment, which resulted in a conflict with the bank: the parties could not reach a compromise concerning bail bond conditions. As a result, when the project was already nearing the deadline, Vnesheconombank froze the allocation of funds. Only Vladimir Putin’s personal involvement in the dispute made it possible for Basic Element to receive the required funds. According to the original plans, the Olympic and Paralympic village was supposed to be completed in early 2013. The complex, however, was put into operation only in November 2013.

After the Olympics, the villages will be converted into a year-round resort complex called Sochnoye. Basic Element declared its intention to sell apartments in the Olympic village at $5,000 per square meter. However, according to analysts’ forecasts, this project will be difficult to implement for a number of reasons. First, hundreds of thousands of square meters of new properties will be on the market after the Olympics. Second, property prices in Sochnoye are almost as high as those in much more developed tourist areas outside of Russia.

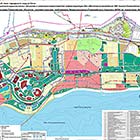

The cemetery in the middle of the Imereti lowlands was first constructed in 1911, when a community of Old Believers was formed by the sea. Many graves are overgrown as a result of an Old Believers’ tradition not to look after graves. In Soviet times, a state-owned farm (sovkhoz) was organized on this land, and since then, Armenian Gregorians, Orthodox Christians, and Muslims have been laid to rest in this cemetery next to Old Believers.

When in 2007, in preparation for the Olympics, the first development plans for the Imereti lowlands were outlined, the existence of the old burial ground was simply overlooked. As a result, the cemetery turned out to be situated right in the middle of the Olympic Park. Residents of the Rossiya state farm village, which is located near the park, began spreading rumors about the authorities’ intention to relocate the village, which stirred up acute indignation among locals. As a result, the development plan was revised, with the burial ground situated next to the park between the Fisht Stadium and the Iceberg Palace.

In April 2008, during a visit of the International Olympic Committee Coordination Commission, a clash broke out in the cemetery between locals and the police. The observation platform offered members of the Commission a view of a virgin piece of land with the burial ground in the middle. Several dozen people, unhappy about the possible demolition of their houses and the unclear conditions of the property buyouts, gathered in the cemetery with banners, calling on the International Olympic Committee for help. The local authorities’ reaction was unexpectedly aggressive: the territory was surrounded by the police, and officials demanded that the banners be put away and threatened demonstrators with consequences.

According to a participant in the rally, representatives of the local administration said: “We will shoot to kill. . . . Beware; sharpshooters are posted everywhere.” In the course of the conflict, an official tried to snatch a pregnant woman’s video camera. A scuffle broke out. People tried to break through the police lines in the direction of the IOC Commission but were stopped. Several participants in the rally were beaten, and crosses on several graves were broken. All demonstrators were arrested, and four of them were fined for participation in an unsanctioned rally.

The cemetery is currently open. The cemetery will be hidden from view with large red fences for the duration of the Games.

The Rosa Khutor Mountain Resort, with its 72 kilometers of trails, is currently the country’s largest mountain ski resort. It includes Olympic mountain ski trails, the Extreme Park, a mountain village, and hotel facilities.

The idea to create a kind of “Russian Courchevel” in Sochi was first floated by Vladimir Potanin, chairman of Interros conglomerate and one of Russia’s richest people. It was mentioned for the first time in 2003, and Potanin himself became one of the most active lobbyists for holding the Olympic Games in Sochi.

Investment in trails and infrastructure was initially projected to be approximately $150 million. Today, total project investment is estimated at $2.2 billion, $1.7 billion of which the state has loaned to Potanin. According to Potanin’s estimates, $500 million has been used to build essential facilities, and the rest has been spent on trails and lifts that will not be used during the Olympics, as well as on hotels, residential properties, roads, and ground protection.

In 2012, a conflict broke out around the Rosa Khutor Resort: Potanin declared that the state had to compensate him for capital outlays for the construction of Olympic facilities either by reducing loan interest rates or by creating a special tax-free economic zone. However, the subject of preferential treatment for investors was hushed up and, according to Rosa Khutor representatives’ most recent estimates, the amount invested in the project might be returned in twenty years rather than in ten, as previously projected.

It is also worth mentioning that the construction of the Rosa Khutor Resort in Sochi attracted the attention of ecologists, since they believe that the development of the territory bordering on the Caucasus State Biosphere Reserve will result in the destruction of unique woodlands and the disruption of animals’ migration paths. However, ecologists’ protests were ignored, and the construction went on.

The “RusSki Gorki” complex for ski jumping came to symbolize the increase in cost of the Sochi Olympics. The original cost of the complex was supposed to be $50 million. In the end, however, it reached $270 million, or five times more than the original estimate. Furthermore, the venue opened for operation two years later than expected. Test events were held in the complex before the construction work was completed.

The government sent a clear message to the investors of the Mountain Carousel Resort and the other major project in the area, Hills City, that investing in the ski jump construction was their social duty. Hills City includes a mountain village for journalists, an additional media center, hotel facilities, and apartments, the latter of which had already been listed for sale before the beginning of the construction. These projects occupy a total of 740,000 square meters, with total investment estimated at approximately $1.3 billion.

Akhmed and Mohamed Bilalov, two brothers close to the regional authorities, became the project’s primary investors. However, when it became evident that the project deadline would be missed and its cost would be considerably higher than expected, Sberbank assumed control over the construction. A badly chosen construction site on unstable ground, which required the placement of a concrete lining on the entire side of the hill, became the key reason for the project’s failure. Furthermore, the Olympstroy Corporation transferred the responsibility to build roads for the complex to the investors, and International Olympic Committee experts insisted on increasing the number of seats. The situation was further complicated by representatives of Marriott brand hotels, who declared that their planned facilities in the Russian Hills village would not be completed before the Olympics. Later, however, Marriott representatives promised to try to complete the work on time.

In February 2013, during Vladimir Putin’s inspection of the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympic venues, he asked what had caused the problems. Officials accompanying the president accused then—vice president of Russia’s Olympic Committee Akhmed Bilalov of causing the delays. A news report concerning this incident was unexpectedly shown on federal TV channels, where problems connected with the construction of Olympic venues were never discussed. Akhmed Bilalov soon left his post, and criminal cases were initiated against both him and his brother. According to different sources, both brothers left Russia.

From a technological point of view, the Sanki sliding center is the most complicated venue of the Olympic construction. The center’s 2,018-meter luge track not only is the world’s longest sliding track but also has the highest track elevation difference of 132 meters. The track was initially supposed to be the world’s fastest as well. However, after the tragedy that took place during the Vancouver Winter Olympics, in which Georgian luge competitor Nodar Kumaritashvili suffered a fatal crash on the track, the idea of setting speed records was abandoned. As a result of the adjustments made to the project, three other slopes were designed in order to prevent competitors from gaining too much speed.

The original cost of the bobsled and luge track was estimated at approximately $150 million. According to Forbes, the Mostovik Company, the project’s primary contractor, declared that because of difficult geological conditions and an extremely tight schedule, the construction cost of the track should amount to at least $400 million. However, after the use of the government coercion, the builders agreed to a compromise and reduced the budget to $280 million. According to a statement by the contractors, they suffered a net loss of around $80 million as a result of their participation in the project. It is worth mentioning that before Sochi, the most expensive bobsled and luge track in the world had been built in Vancouver for the 2010 Winter Olympics. Its cost amounted to $118 million.

The construction itself started in a rush, without either approval for the project documentation or the permit for clearing 27 hectares of forest to make way for the track. International Olympic Committee experts have called Sanki the riskiest project of the Sochi Olympics.

Furthermore, the first tests, which were held in March 2012 on an uncompleted track, were three months behind schedule. A few months later, a criminal case was initiated in connection with the increase in construction cost of the bobsled and luge track. Mostovik and Olympstroy top management were accused of embezzling $70 million. In the fall of 2013, the criminal case was dropped.

In 2008, several environmental organizations mounted a serious protest against the construction of a ski and biathlon complex called Laura. The Russian chapter of Greenpeace declared that the development of these territories will negatively affect the adjoining Caucasus State Biosphere Reserve, which protects the region’s natural heritage. The authorities decided to accommodate the ecologists: Vladimir Putin personally promised to make the necessary adjustments to the construction project. However, the compromise solution to move the construction one kilometer away from the initial site did not satisfy conservationists.

As a result, the project was put on hold for two years. Among other reasons for suspending the construction was the Belarusian authorities’ refusal to finance the project. In 2006, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko advanced an initiative to create a “small piece of Belarus” in Sochi. The Belarusian company Triple was supposed to build a 20,000-seat biathlon complex occupying a territory of 40 hectares. The project cost was estimated at approximately $10 million. However, the Russian-Belarusian oil and gas conflict, in which Russia refused to supply Belarus with subsidized oil, resulted in the abandonment of the project.

Thus, the project was transferred to the control of Gazprom, which chose a different location for the arena and combined it with a 16,000-seat ski complex. The joint project became part of the Laura mountain ski resort, which also belongs to the gas corporation. Later, however, the project’s plans were readjusted again, and consequently, the number of spectators the complex will be able to accommodate was reduced to 7,500, while the project cost rose to $20 million. Currently, total investment in Laura is estimated at $1 billion.

According to foreign athletes who participated in a test event at Laura, the venue will be one of the smallest international biathlon complexes in operation today, which is very strange, since the biathlon is one of the most popular winter sports. Just for comparison, the Czech Nové Město biathlon complex accommodates 27,000 people.

Furthermore, the 2012–2013 test events demonstrated that the trails are not well-designed: most athletes found them too difficult. The 2014 Sochi Organizing Committee, along with international cross-country ski and biathlon federations, are promising to make all necessary adjustments before the Olympics.

The combined Adler—Krasnaya Polyana railroad and highway, connecting the Adler coastal district with Krasnaya Polyana village, is the world’s most expensive road. In 2006, its construction cost amounted to $3.8 billion. However, by 2009, its cost had increased by two and a half times, reaching $9.4 billion. The length of the highway is 48.2 kilometers. Thus, one kilometer of the road cost around $200 million, a world record.

For comparison, the American program to reach Mars and operate the Mars rover Curiosity there cost about three and a half times less than the cost of building the Adler—Krasnaya Polyana transportation corridor. According to Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, with the money spent on this highway, one could build 5.5 million square meters of housing and provide living space for 275,000 people.

President of Russian Railways Vladimir Yakunin, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s close friend, was responsible for the construction of the highway. Officially, the high cost was explained by difficult working conditions: two-thirds of the highway consists of tunnels and bridges. However, according to numerous media reports, Russian Railways generously provided its contractors with multibillion-dollar contracts without any tenders.

Originally, the necessity of building a second major road from Adler to Krasnaya Polyana, where the mountain sports competitions will take place, was dictated by International Olympic Committee requirements. The Russian authorities, however, approached this question creatively by combining an automobile road with a railroad. Furthermore, they chose the most difficult and expensive way of building the highway by routing it through the Mzymta Valley. All less-costly alternatives were rejected by the authorities.

The construction started in 2008 with several serious violations of Russian law. First, construction began without formal project approval, necessary permission documentation, or an environmental impact assessment. Second, the road was slated to run through the most valuable parts of the Sochi National Park, which contains unique tree varieties that are on the endangered species list. Local ecologists tried to stop illegal forest clearing by calling the police. However, forest clearing resumed soon afterward, and the ecologists themselves, who tried to prevent centuries-old boxwoods from being cut down, found themselves behind bars.

Companies involved in the construction of the highway promised United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) representatives that they would implement an ambitious program to restore the Mzymta River ecosystem. However, in reality, after destroying tens of thousands of trees, Russian Railways confined itself to planting a few hundred young boxwood plants, most of which died soon afterward.

From the point of view of power supply, Adler is one of Russia’s most problematic cities, one where power cuts are a regular occurrence. This is why a new 360 MW thermal power plant was supposed to be built in order to supply the Olympic facilities with heat and power.

In September 2008, Gazoenergeticheskaya Kompaniya, a company affiliated with Gazprom, was given a no-bid contract to build the Adler thermal power plant. TEK Mosenergo, which is also controlled by Gazprom, was named the primary contractor. Investment was estimated at $900 million, and the plant was initially supposed to begin operation in May 2012. However, construction, which began in the fall of 2009, was complicated by difficult conditions, including limited space and heightened seismic activity.

In 2012, companies controlled by Arkady and Boris Rotenberg, brothers who are President Putin’s childhood friends, bought TEK Mosenergo from Gazprom. It is worth mentioning that before the deal was made, during a meeting of the Supervisory Council of the VTB Bank, Putin pointed out that the bank would invest $630 million in the construction of the Adler thermal power plant. And although the total cost of the construction in dollars remained the same, its cost in rubles increased from 23 to 28 billion.

As in many other cases, deadlines were repeatedly pushed back. Furthermore, as a result of the change of ownership, many qualified specialists left TEK Mosenergo. The power plant began working at full capacity only in January 2013. However, once the delegation of Russian government officials left Sochi, the plant was switched off again. In April 2013, VTB Bank allocated an additional $80 million credit to Gazprom to finish the construction of the Adler thermal power plant.

The Kudepsta Thermoelectric Power Plant is one of four electric plants that were supposed to be built in Sochi for the 2014 Olympics. The project proved to be unsuccessful: attempts at realizing it have been hindered by delays, interdepartmental conflicts, repeated budget increases, and protests by local residents and environmental activists.

In 2010, the TGK-2 Company declared its intention to build the 360 MW Kudepsta Thermoelectric Power Plant (Sintez Group, owned by Russian Federation Council member Leonid Lebedev, holds the controlling stake in TGK-2). The new thermoelectric power plant was supposed to be located in the quiet resort village of Kudepsta, approximately 100 meters from residential homes. Local residents were categorically against the installation of an industrial facility in their backyards. Sochi’s city administration then suggested an alternative site to the investors, which was located 4.5 kilometers from the village. Because an agreement concerning the construction site could not be reached, TGK-2 abandoned the project. The company’s management accused the local authorities of hindering the project and declared that the existing conditions made it impossible for the company to complete it before 2014.

The little-known company Kontsern Vneshenergosnab, the annual income of which amounts to approximately $50,000, had for some time been claiming the right to build the thermoelectric power plant. However, the required investment in the Kudepsta project was estimated to be $300 million at least. As a result, the project was given to Gazenergostroy. Although several offshore companies own the controlling shares in Gazernergostroy, according to unofficial sources, this company is close to Gazprom’s top management. The new investor estimated the cost of the power plant to be approximately $700 million.

The news about the resumption of the project resulted in a new wave of protests in Kudepsta village, despite the fact that the new site had been moved away from the residential area by half a kilometer. Construction equipment was supposed to be delivered in the fall of 2012. However, local ecologists and activists organized a 24-hour watch near the construction site to try to prevent employees of Gazenergostroy from conducting geological research without the necessary permits. At the same time, an environmental impact assessment was delayed as well. The construction permit was not issued until April 2013, when all planned deadlines had already passed. However, the company insisted on starting the construction work. The situation was aggravated by the use of force by the company’s security personnel against local activists in order to enable heavy machinery to access the site. However, the company’s efforts ultimately proved unsuccessful, since one month later, the authorities declared that the Kudepsta project would be abandoned.

The Imereti Port might be called the most useless and unlucky project of the Sochi Olympics. The idea to build a seaport stemmed largely from a calculation error concerning freight delivery to the Olympic construction sites. It turned out that the port would have to handle one-third less building material than had previously been estimated, and consequently, railroad and highway transport could manage such delivery on their own. However, by the time the error was found, the project had already been started. Oleg Deripaska’s Basic Element Company intended to invest around $200 million in the construction of piers and port infrastructure. The same amount was supposed to be allocated from the federal budget for building breakwaters.

In December 2009, when the seaport was half completed, a strong storm that hit the Imereti lowlands destroyed the unfinished breakwaters. Eight building cranes were washed away from the pier by the sea. A diving boat with three crewmen capsized. Their bodies were never found.

Officially, the port’s destruction was caused by force-majeure circumstances: this was allegedly the strongest storm of the twenty-first-century. However, according to independent experts, the port’s destruction was caused by either design faults or poor quality of construction. Furthermore, ecologists believe that the port is in a bad location. The decision was then made to rebuild the port near the Mzymta River delta, where deep-sea canyons increase the strength of storms. Also, the port’s construction has prevented gravel from the river from being washed onto the shore. Consequently, according to experts’ forecasts, if no special measures are taken to fill in the nearshore, in five to seven years, the beach width here will decrease by one-half.

The amount of insurance benefits received by Basic Element for damages has not been disclosed. According to the most recent reports, the investor’s expenses reached $300 million, including state loans. Oleg Deripaska openly declared that the port was clearly unprofitable: although its cargo turnover was supposed to be 14 million tons, the port has only handled 3 million tons since its construction. The businessman tried to accuse the Olympstroy state corporation of miscalculation and demanded that he be paid $130 million in compensation for damages. His efforts, however, did not succeed.

After the Olympics, Basic Element intends to convert the cargo port into a yacht marina, for which the company will invest another $100 million. The search for foreign partners has so far proved unsuccessful. It is quite possible that after the Olympics, the state will be able to seize the port for debts and for further use as the Sochi port’s cargo area.

Russia’s bid to host the Olympics included the proposal for construction of two cargo ports in the Imereti lowlands in order to allow the delivery of construction materials for Olympic venues. One of the ports has already been built in the Mzymta River delta. A second port was initially supposed to be located in the Psou River delta at the Russian-Abkhaz border but was later moved to the center of the Rossiya state farm, right next to a residential area. Local authorities claimed that the second cargo port area would only function on a temporary basis, during deliveries of construction and building materials.

However, as ecologists and opposition activists found out later, the Transport Ministry was lobbying for the construction of a permanent cargo port in this area under the pretext of preparing for the Olympics. The prospect of living close to an industrial site, which would obviously complicate the development of tourism, frightened not only local residents but also some Olympic investors, who joined the campaign against the construction of the port. They were also joined by ecologists, who contended that the construction of a second cargo port would result in the complete destruction of the shoreline and the unique intercoastal ecosystem of the Imereti lowlands, as well as the loss of some species of plants. After a series of protests, the authorities acknowledged that a second cargo port was not strictly necessary, and it was eliminated from the construction program for Olympic facilities.

One of Russia’s pledges to the International Olympic Committee was that it would comply with the so-called “zero-waste” policy at Olympic venues. In practice, this meant closing two landfills in the city and implementing a modern system of waste disposal and management. Oleg Deripaska’s Tonnelny Otriad-44 Company was responsible for project implementation. Investment was supposed to be approximately $500 million.

According to the project documentation, a new solid household waste disposal facility was supposed to be located between the Boo and Khobza rivers near the village of Vardane. Trying to save money on road building, developers chose a construction site in close proximity to residential houses, which resulted in a wave of public outrage. According to ecologists, the waste management technology chosen for the facility would have been unsafe for both the environment and local residents. Local activists regularly organized protest rallies, one of which ended in a clash with the police (video).

To the protesters’ surprise, they were supported by the Russian Accounts Chamber and several State Duma deputies. According to some sources, the reason for this support was that a number of top officials owned land near the site of the future waste management facility. In any case, the idea of constructing a solid household waste disposal facility in Vardane was abandoned.

Investors used whatever little time they had left to build a small garbage recycling plant in the middle of the city, which is only capable of sorting a small percentage of waste. One landfill, situated in the Adler district, was closed. However, trash is still being illegally dumped in the second landfill, despite a pledge to rehabilitate this site by the end of 2013. The authorities ordered that part of the waste be removed from the city and transferred to one of the districts of the Krasnodar region. As a result, waste rates have tripled, and the number of illegal dumps in Sochi has increased.

The new village of Nekrasovskoye, which contains 112 houses, was built under pressure from local residents whose lands had fallen within the construction area of Olympic venues. The story of the village’s creation is very dramatic. Before Sochi was selected as the host city of the Winter Olympics, governor of the Krasnodar region Alexander Tkachev declared that not one house would be sacrificed to the Olympics. However, soon afterward, it became known that some houses in the Imereti lowlands fell within the construction zone and would need to be relocated. At the same time, the authorities were unable to provide concrete details regarding the procedures of property appraisal, buyout, and relocation.

In 2008–2009, several mass protests against forced relocation took place in Imeretinka. The initial relocation plan consisted of moving residents from the seaside into the mountains. However, after a series of rallies that attracted the attention of the International Olympic Committee, the decision was made to build a village not far from the houses that were supposed to be demolished. Additionally, the number of houses slated for demolition was reduced.

However, not many residents of the condemned houses agreed to move to Nekrasovskoye village. Many complained of the poor quality of the new construction. The authorities offered monetary compensation to those who refused to move to the new village. The average land price was $50,000 per acre (100 square meters). House prices were estimated separately. In some cases, the compensation amounted to $1.5–2 million. As a result, although Nekrasovskoye village was entirely populated in 2010, its residents today still experience troubles with their water and gas supply.

The Olympic construction affected the interests of approximately 3,000 Sochi property owners altogether, for whom the authorities built seven similar villages. Only one-third of potential settlers agreed to relocate, whereas the rest preferred monetary compensation. The authorities spent a total sum of around $1 billion on the relocation program.

During the construction launch of a new resort complex in the Imereti lowlands, Sergei Gaplikov, president of the Olympstroy state corporation, said that the implementation of this project was strategically significant, since without it the Sochi Olympic Games “might be challenged.” Despite this fact, however, the construction did not go smoothly by any means.

Initially, Telman Ismailov, a businessman and chairman of the Russian AST Group, was supposed to assume the role of primary investor in the new resort complex. In 2009, Ismailov invested around $1 billion in the construction of one of the world’s most expensive luxury hotels, the Mardan Palace in Turkey. According to unofficial sources, after hosting a lavish party attended by Hollywood stars for the opening of the hotel, Ismailov enraged Vladimir Putin—the national leader did not like that the businessman had invested such huge sums abroad. Ismailov had to part with the Cherkizovsky market in Moscow, which he used to own, and leave the country.

In 2010, it became known that in order to be able to return to Russia, Ismailov was prepared to invest money in the construction of various Olympic venues and to build a 5,000-room resort complex in the Imereti lowlands priced at $1 billion. The project, however, was put on hold at the initial design stage and transferred to the Top Project Company, which is a part of Viktor Vekselberg’s Renova Group. The new investor reduced the number of rooms to 3,600 and brought the amount of investment down to $600 million, more than half of which was provided by Vnesheconombank.

Since most investors engaged in building the Olympic Park’s infrastructure see their participation in this project as a social duty and a token of loyalty to the state rather than as an opportunity to develop a commercially viable project, many experts doubt that the resort business in the Imereti lowlands will prove to be successful. Many investors make no secret of the fact that they hope to get their money back, not by developing the hospitality industry, but by subsequently selling off the property at a profit. Top Project representatives declared that they were planning to sell all of the AZIMUT Hotels Sochi complex apartments within ten years. The construction was supposed to be completed in June 2013. However, according to Russian news sources, the complex was only put into operation in December 2013.

The Chernomorets Spa Hotel was named after the Chernomorets tourist destination—now a boarding house—which is located nearby and used to be very popular in Soviet times. The current owners of the boarding house had been planning a renovation even before Sochi won the bid to host the Olympics. However, instead of an inflow of investment, the city’s new status brought them unexpected difficulties.

According to Sochi’s original bid to host the Olympics, a second cargo port was supposed to be built in close proximity to the boarding house, which would have put an end to its future as a tourist destination. Later, however, the authorities abandoned the idea of building a port, included the Chernomorets boarding house in the construction program in preparation for the Olympics, and authorized its owners to build another hotel on the land designated for port infrastructure.

The owners drew up plans for a five-star hotel and spa under the Chernomorets name that would have cost several million dollars. This project, however, never came to life. A conflict broke out between the administration of the Krasnodar region and the Olympstroy management in connection with the site intended for the construction of the hotel. As a result, the project was transferred to the management of Yuri Zhukov, the founder of real estate developer PIK Group. Zhukov is believed to be close to Deputy Prime Minister Dmitri Kozak, who is responsible for Olympic preparations. Zhukov, however, considered his participation in the construction of Olympic hotels a rather unprofitable enterprise and abandoned the project. As a result, the land intended for the construction of a cargo port was transferred to the OlymPlus Company, the sole owner of which is Krasnodar businessman Soslan Sundukov. The Chernomorets boarding house itself is connected with different lawsuits.

After a series of changes of ownership, the Chernomorets property came under the control of top managers of the Russian “daughter bank” of Cyprus Popular Bank, the island’s second-largest bank. However, by that time, it had become evident that the hotel and spa would not be completed before 2014, and the project was eliminated from the Olympic program. The authorities terminated their lease of coastal land and tried to restore state ownership of the boarding house. The Chernomorets owners are currently trying to challenge this decision in court. At the same time, despite lawsuits, the construction of several small cottages is currently under way on the location of the old boarding house. Local residents regularly see Russian top government officials visiting the construction site.

The organizers of the Sochi Olympics consider the Russian International Olympic University (RIOU) to be the main humanitarian legacy of the Games. RIOU is the only higher education institution in the world to specialize in training specialists in the field of sports management; Interros Company head Vladimir Potanin has called RIOU the “Russian Harvard.” President Vladimir Putin was named head of the University Board of Trustees, and International Olympic Committee President Jacques Rogge took part in the ceremonial laying of the first foundation stone of RIOU. Total investment in the construction of the complex is $500 million, with $150 million being provided by Interros and the rest in the form of a long-term loan by Sberbank.

The University was supposed to be built in the Imereti lowlands, not far from the Olympic Park. Later, however, the plans changed. The construction area was moved to the grounds of a former health resort named after Maurice Thorez in downtown Sochi. This idea provoked protests by local residents, since this small piece of land was the only part of the city of Sochi preserved in its pre-1917 state. Local residents’ favorite pine walk along the seafront was to be cleared as well. Most of all, Sochi residents were outraged by the investors’ intention to build residential apartments and hotels in addition to the academic building. According to local architects, further densification of the Sochi downtown was unacceptable and violated city development regulations.

In order to preserve the city’s historical downtown, Sochi activists organized rallies and sent messages to the authorities. Their efforts did not result in much: although the idea of clearing the pine walk was abandoned, the health resort buildings were eliminated from the list of historical landmarks and demolished. A magnolia alley that had been planted in commemoration of the 1945 World War II victory was cut down. Four fifteen-story buildings were constructed on the site of the old health resort, with only one of them slated for use as an academic building and three others intended to be used as hotels.

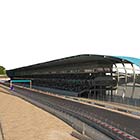

In 2010, the decision was made to build a Formula One track in Sochi. The contract for the Russian Grand Prix was signed by president of Formula One Management Bernard Ecclestone, governor of the Krasnodar region Alexander Tkachev, and a representative of the Omega Construction Technology Transfer Center of Krasnodar Krai. The track was supposed to connect the Olympic park arenas, which were under construction at the time. Despite the prestige of the championship, doubts were expressed in the media about the viability of developing another project in such a geographically limited area. The proposed deadlines gave rise to more doubts: the first race was supposed to be held in the fall of 2014.

The initial cost of the construction of the track was estimated at $200 million. Later, however, the cost amounted to $350 million, an increase explained by the omission from the original estimates of a number of technical specifications of the project’s developer, German company Tilke GmbH. The construction work was as good as suspended in the fall of 2013 as a result of the preparations of the Olympic park for the 2014 Winter Olympics. The 2014 Russian Grand Prix was again put in jeopardy when it turned out that the organizers had missed the deadline for filing their application with the International Automobile Association. In the end, however, this problem was solved.

According to preliminary estimates, holding the Russian Grand Prix in Sochi will cause a loss of $55 million for the organizers, which will be reimbursed from the budget of the Krasnodar region. Furthermore, many automobile experts doubt that Formula One could enjoy great popularity in Russia, not least because of the exorbitant resort prices. A visit to Sochi is projected to cost Russian racing fans almost twice as much as a trip to the Hungarian Grand Prix.

In preparation for the 2014 Olympics, Sochi’s oldest health resort, the Caucasian Riviera, was supposed to be transformed into a luxury five-star hotel. However, the reconstruction project was never completed. Furthermore, the buildings, which used to be listed on historical and cultural landmark registers, were destroyed, and consequently, tensions arose between the investors and the authorities.

The Caucasian Riviera health resort opened in downtown Sochi on June 14, 1909, and quickly became a highly popular vacation spot among the Russian intelligentsia, especially during World War I, when access to European resorts became difficult. Isaak Babel, Mikhail Zoshchenko, Ilya Ilf, Evgeny Petrov, Evgeny Shvarts, and Vladimir Mayakovsky used to come to the Caucasian Riviera. In the second part of the twentieth century, however, the resort fell into disrepair until the late 1990s when it was purchased by businessman and former Russian State Duma deputy Vladimir Bryntsalov.

In 2010, the Caucasian Riviera was included in the plans for preparation for the 2014 Sochi Olympics. Investors pledged $1.5 billion to the project in order to replace the long-standing health resort with a 250-room luxury five-star hotel. Contractors got the permit for reconstruction of the historical landmark from the Russian Federal Mass Communications Oversight and Cultural Heritage Protection Service. However, during reconstruction work, resort buildings were partially pulled down and redesigned, and new parts were added to them in violation of the regulations and without consideration of the historical value of the landmark. As a result, the cultural heritage of the health resort has been irreparably lost.

In 2012, local authorities accused the investors of performing illegal construction work. The construction was put on hold, and the health resort itself was eliminated from the Sochi Olympics preparation plans. In August 2013, the decision was made to completely demolish the 16,000 square meter reconstruction.

The Southern Cultures Botanical Garden is one of the most beautiful landscape parks on the Black Sea coast of the Caucasus. It was founded in 1910 by General Daniil Drachevsky, the governor of St. Petersburg, on his Sochi estate.

In Soviet times, the Southern Cultures Botanical Garden contained the country’s largest collection of decorative exotic plants. However, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the park fell into decline. In 2001, a strong tornado destroyed 40 percent of all plants in the botanical garden, after which 5 hectares of the park territory were appropriated by government officials, judges, and the military. In 2010, the state-owned enterprise that was responsible for the park was certificated bankrupt. A company connected with Basic Element chairman Oleg Deripaska, whose holdings are actively participating in the construction of Olympic venues, is the park’s main creditor.

However, the businessman’s attempts to confiscate the park for debts did not succeed. Instead, the park’s lands were transferred to Sochi National Park, with the exception of the century-old sycamore alley, which was badly affected by its proximity to Olympic construction sites (the park was surrounded by several concrete and asphalt factories). The authorities allocated $2 million for the reconstruction of the botanical garden, but by the fall of 2013, work had not yet started. Local activists fear that before the Olympics begin, the unique botanical garden will be transformed into an amusement park.

Keep exploring!

Check off more to take a quiz